Two-Period Endowment Economy

The consumer's problem in a simple two-period closed economy.

Previously, we looked at a one period model economy where a representative consumer makes a decision about the tradeoff between leisure and labor, and a firm makes decisions about production. Here, we want to add time into the mix, so that we can use our model to think about savings and investment. To make the additions more clear, we will temporarily strip away the details about leisure and production, and look at what is called an “endowment economy”.

In an endowment economy, consumption goods aren’t produced; they just fall from the sky. Our representative consumer is endowed with some amount of exogenous income in each period, and must choose how to split these resources between past and future consumption.

Definition of the representative consumer's problem with lump-sum taxes

Taking the real interest rate and income as given $\lbrace r,y,y’\rbrace$, the consumer chooses consumption in the first period, savings, and consumption in the second period $\lbrace c, c’, s\rbrace$ to solve:

\[\begin{aligned} \max_{\lbrace c, c', s\rbrace } & U(c,c') \\ \text{s.t. } & c\geq0,\ \ \ c'\geq0\\ & c + s\leq y \\ & c'\leq y' + (1+r)\cdot s \\ \end{aligned}\]We also represent this problem with a single intertemporal budget constraint by solving for $s$ and combining the two per-period budget constraints:

\[\begin{aligned} \max_{\lbrace c, c', s\rbrace } & U(c,c') \\ \text{s.t. } & c\geq0,\ \ \ c'\geq0\\ & c + \frac{c'}{1+r}\leq y +\frac{y'}{1+r}\\ \end{aligned}\]Assuming an interior solution, the solution is characterized by the following equations:

\[c + \frac{c'}{1+r} = y +\frac{y'}{1+r} \\ MRS_{c,c'}\equiv\frac{MU_{c}}{MU_{c'}}=1+r\]The gross real interest rate $1+r$ is the marginal rate of transformation between consumption today and consumption in the future. From the consumer’s perspective, the interest rate can be thought of as the cost of moving resources back in time from their future self.

Details about the problem.

Any constrained optimization problem has a set of choice variables, constraints which limit what values those choices can take, and an optimand (the thing which is optimized).

Choices

In this endowment economy, the consumer chooses how much to consume each period, and

- First period consumption: $c$

- Second period consumption: $c’$

- Savings: $s$

- When the budget constraint binds, savings will simply be the difference between first-period income and consumption.

Constraints:

-

The Non-negativity Constraints: You can’t consume negative amounts.

\[c\geq0 \\ c'\geq0\]- Note that savings $s$ is allowed to be negative. Negative savings means the consumer is borrowing money in the first period.

-

The First Period Budget Constraint - Income can be split between consumption and savings.

\[c + s\leq y\] -

The Second Period Budget Constraint - Consumption in the second period is limited by second period income, plus the returns from first-period savings.

\[c'\leq y' + (1+r)\cdot s\]- If the consumer saves $1$ unit of goods in the first period, then their second-period income is increased by $1+r$ units.

- If the consumer borrows $1$ unit of goods in the first period (which means $s=-1$), then they must pay back $1+r$ units in the second period.

The two per-period budget constraints can also be combined into a single intertemporal budget constraint:

\[c + \frac{c'}{1+r}\leq y +\frac{y'}{1+r}\]The left side of this equation is the present value of lifetime consumption, while the right-hand side is the present value of lifetime income.

The Optimand (Utility)

The consumer is trying to maximize a utility function which represents their preferences for consumption across time.

\[U(c,c')\]We would like this utility function to have some of the same nice properties from chapters 4 and 5:

- More consumption is preferred to less (meaning U is strictly increasing).

- The Representative Consumer has a preference for diversity (U is concave), which here means that the consumer wants to “smooth” their consumption across time.

- Consumption in each period are normal goods.

Although we could use any function of $c$ and $c’$ here, when looking at intertemporal decision-making, we typically use a utility function which looks something like this:

\[U(c,c') = u(c) + \beta u(c')\]where $\beta \in (0,1)$ is the “time discount factor”.

When we write a utility function like this, we’re saying that the person’s preferences within each period (represented by little-u per-period utility $u(\cdot)$) aren’t changing. Rather, the important difference between the person’s current self and their future self is that they care a bit less about their future self when they make decisions today. If you’ve ever stayed up too late or drank too much, you’ve probably felt the next morning that the gain in happiness last night is exceeded by the reduction in happiness you feel come morning. So why make such a decision? Perhaps it is because your $\beta$ is less than one. When you made that decision, you “discounted” the preferences of your future self.

If $\beta=1$, the person is very patient and equally values their preferences in each period. If $\beta$ is very low, close to zero, then the person makes decisions in the first period with little regard to how it will affect their future self.

Effects of Shocks

An increase in $y$:

- First period consumption $c$ increases. The consumer has more income, and so spends more.

- Second period consumption $c’$ also increases because we assume the consumer prefers to smooth their consumption over time.

- Savings $s$ increases. This is how the consumer shifts some of that extra income into the future.

An increase in $y’$:

- Both $c$ and $c’$ increase, as above.

- From the inter-temporal perspective, either shock is an increase to the exogenous present-value income: $y+\frac{y’}{1+r}$

- On the other hand, savings $s$ decreases. If savings is negative, then borrowing increases. When future income goes up, the consumer doesn’t need to save as much for the future. Or you can think of this as the consumer shifting some of their future income into the present by borrowing money.

The effects of an increase in the real interest rate are more complicated.

- A higher $r$ decreases the present value of lifetime income $y+\frac{y’}{1+r}$, because that future income is more difficult to bring into the present.

- On the other hand, it increases the future value of lifetime income $(1+r)y+y’$ because any income saved results in higher returns tomorrow.

- Thirdly, there is a substitution effect. In terms of present-value, the cost of one unit of future consumption is $\frac{1}{1+r}$ units of current consumption. An increase in the interest rate makes future consumption relatively ‘cheaper’ in some sense.

In general, an increase in the real interest rate will make the consumer want to shift their consumption from the present into the future. But in some cases, it is possible for the above income and substitution effects to cancel each other out.

| Borrower | Saver | |

|---|---|---|

| $c$ | $\downarrow$ | $\downarrow$ ? |

| $c’$ | $\uparrow$ ? | $\uparrow$ |

Adding Lump-sum Taxes and a Government Budget

Adding lump-sum taxes to the consumer’s problem is easy. From the consumer’s perspective, there isn’t much difference between an exogenous $y$ versus an exogenous $(y-T)$

If the consumer pays a lump-sum tax of $T$ in the first period, and a lump-sum tax of $T’$ in the second period, then consumer’s per-period budget constraints become

\[c + s\leq (y-T)\] \[c'\leq (y'-T') + (1+r)\cdot s\]And the intertemporal budget constraint becomes:

\[c + \frac{c'}{1+r}\leq (y-T) +\frac{(y'-T')}{1+r}\]Structurally, this is the same as what we have above. It’s just that the right-hand side is now the present-value of lifetime disposable income.

An increase to $T$ or $T’$ has the same effect as a decrease in $Y$ or $Y’$.

The Government’s Budget.

With lump sum taxes, the government’s budget in this simple economy is that:

\[G = T-s_g \\ G' = T'+(1+r)s_g\]Where $(G,G’)$ are exogenous government spending requirements, and $s_g$ is government savings.

We can also combine this into a single intertemporal government budget constraint:

\[G + \frac{G'}{1+r} = T + \frac{T'}{1+r}\]Ricardian Equivalence

Recall from above that shocks to $Y$ or $Y’$ have similar effects. In this simple model, consumption levels in each period are determined only by the present value of a person’s income across both periods of their life.

Now suppose that the government wants to change the timing of taxes without changing $G$ or $G’$. If they reduce taxes by $1$ unit today (or equivalently lump-sum transfer one unit to consumer’s today), then they must increase taxes by $(1+r)$ units tomorrow to keep the budget constraint satisfied:

\[G + \frac{G'}{1+r} = T + \frac{T'}{1+r} = T-1 + \frac{T'+(1+r)}{1+r}\]How does this effect the consumer’s present-value lifetime income? It doesn’t:

\[(y-(T-1)) +\frac{(y'-(T'+1+r))}{1+r} = (y-T) +\frac{(y'-T')}{1+r}\]Therefore, because the present-value of taxes remains the same, this change in the timing of taxes won’t affect the consumer’s intertemporal budget constraint. It won’t affect the optimal $(c,c’)$ bundle, and so won’t affect the consumer’s utility.

Ricardian Equivalence is this notion that it’s the present-value of taxes, rather than the timing of taxes, that matters for consumption patterns and welfare.

The only thing that changes in the consumer’s problem is the level of savings. – If we shift tax burden from tomorrrow into today, consumer knows that taxes will be lower in the future, and so borrows more/saves less – If we shift tax burden from today into tommorrow, then consumer knows taxes will ber higher in the future, and so saves more/borrows less.

How well does this hold up?

The model predicts that it is increases in permanent income which increase consumption, and that a temporary increase in income will instead mostly just increase savings.

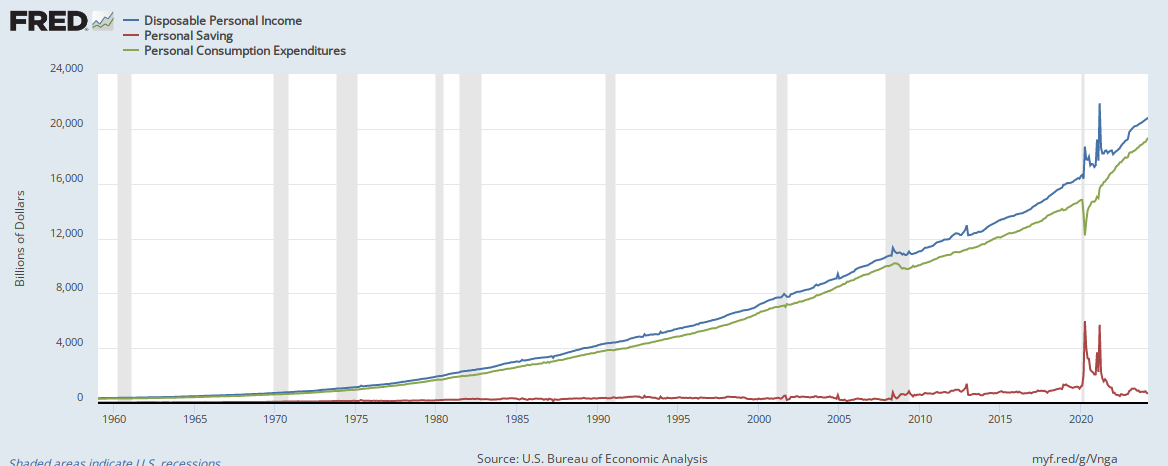

On the one hand, this story seems to hold up when we look at aggregate statistics from 2020:

In response to the COVID-19 epidemic, the economy retracted, and many people lost their jobs. But because of large government transfer programs, disposable personal income actually went up during the 2020 recession. This spike in disposable income didn’t translate to a spike in consumption, but rather a massive increase in savings. This is consistent with what our model tells us.

But contrary to the aggregate picture and to what Ricardian Equivalence tells us, it’s also very easy to think of individual cases where the timing of those transfers did matter - individual households which where made better off by having those transfers at that time, even if future income falls as a result. In chapter 10, we discuss how credit-market imperfections can break this implication of Ricardian Equivalence.