Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence

BibTeX

@article{lloyd2005superspreading,

title={Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence},

author={Lloyd-Smith, James O and Schreiber, Sebastian J and Kopp, P Ekkehard and Getz, Wayne M},

journal={Nature},

volume={438},

number={7066},

pages={355--359},

year={2005},

publisher={Nature Publishing Group}

}

Abstract

Population-level analyses often use average quantities to describe heterogeneous systems, particularly when variation does not arise from identifiable groups. A prominent example, central to our current understanding of epidemic spread, is the basic reproductive number, R0, which is defined as the mean number of infections caused by an infected individual in a susceptible population. Population estimates of R0 can obscure considerable individual variation in infectiousness, as highlighted during the global emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) by numerous ‘superspreading events’ in which certain individuals infected unusually large numbers of secondary cases. For diseases transmitted by non-sexual direct contacts, such as SARS or smallpox, individual variation is difficult to measure empirically, and thus its importance for outbreak dynamics has been unclear. Here we present an integrated theoretical and statistical analysis of the influence of individual variation in infectiousness on disease emergence. Using contact tracing data from eight directly transmitted diseases, we show that the distribution of individual infectiousness around R0 is often highly skewed. Model predictions accounting for this variation differ sharply from average-based approaches, with disease extinction more likely and outbreaks rarer but more explosive. Using these models, we explore implications for outbreak control, showing that individual-specific control measures outperform population-wide measures. Moreover, the dramatic improvements achieved through targeted control policies emphasize the need to identify predictive correlates of higher infectiousness. Our findings indicate that superspreading is a normal feature of disease spread, and to frame ongoing discussion we propose a rigorous definition for superspreading events and a method to predict their frequency.

My Notes

Summary

the basic reproductive number $R_0$ is the mean number of infections caused by an infected individual in a susceptible population. But this is a population average. Individual variation in spread is important and empirically highly skewed. This gives rise to the phenomenon of “superspreaders”. This skewness makes “disease extinction more likely and outbreaks rarer but more explosive.”

First Page

super dense and somewhat less elgant than the examples I was previously looking at. Seems like a feature of Nature, The abstract is as big as the entire first page in those examples of good econ writing.

Interesting excerpts

Rule of thumb from other literature :

a general ‘20/80 rule’ (whereby 20% of cases cause 80% of transmission) and to the influential concept of high-risk ‘core groups

Weaknesses of contact-matrix and similar approaches:

For directly transmitted infections, however, the overall infectiousness of each case… arises from a complex mixture of host, pathogen and environmental factors. Consequently, the degree of infectiousness is distributed continuously in any population and, crucially, distinct risk groups often cannot be defined a priori. This impedes the conventional approach to adding heterogeneity to epidemic models, in which populations are divided into homogeneous subgroups.

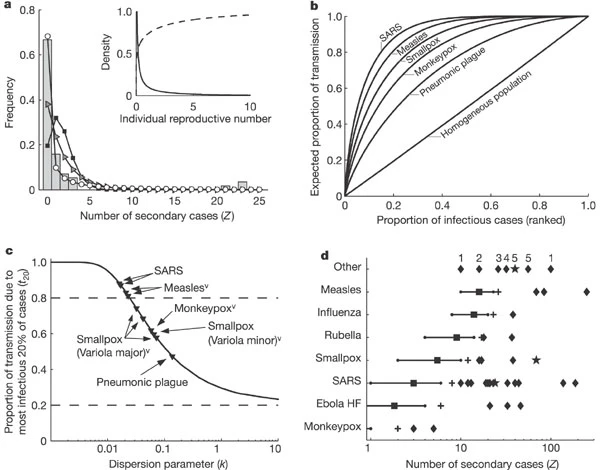

For the Singapore outbreak, the maximum-likelihood estimate k̂ is 0.16 (90% confidence interval 0.11–0.64), indicating an underlying distribution of ν that is highly overdispersed (Fig. 1a, inset). According to this analysis, the great majority of SARS cases in Singapore were barely infectious (73% had ν < 1) but a small proportion were highly infectious (6% had ν > 8). This is consistent with field reports from SARS-afflicted regions5,6 but contrasts with published SARS models9,10,25,26.

figure 1a, showing variation in infection spread:

standard model of spread of disease doesn’t match observed patterns

Comparing results for eight directly transmitted infections reveals the differing degree of individual variation among diseases and outbreak settings … The Poisson offspring distribution is almost always strongly rejected. The geometric model has considerable support for several data sets, which indicates significant individual variation in transmission rates because real infectious periods are less dispersed than the exponential distribution. The negative binomial model is selected decisively for several data sets, and enables comparative study of diseases through the dispersion parameter

measles in highly vaccinated population, and SARS both show high variation, with “narrow confidence intervals excluding the conventional models”

super spreader events (SSEs)

Unrecognized or misdiagnosed illness is the most common cause of these [Super-Spreader Events], followed by alternative modes of spread (especially airborne), high contact rates, and co-infections that aid transmission. High pathogen load or shedding rates are occasionally implicated, but are rarely measured.

Accordingly, when individual variation is large, extinction occurs rapidly or not at all

Pattern of SARS 1 outbreaks:

For outbreaks avoiding stochastic extinction, epidemic growth rates strongly depend on variation in ν… Diseases with high individual variation show infrequent but explosive epidemics after introduction of a single case. This pattern recalls SARS in 2003, for which many settings experienced no epidemic despite unprotected exposure to SARS cases27,28, whereas a few cities suffered explosive outbreaks Our results, using $k̂ = 0.16$ for SARS, explain this simply by the presence or absence of high-$ν$ individuals in the early generations of each outbreak

Comparing the models to actual containment policies:

To assess the realism of these idealized control scenarios, we analysed contact tracing data from four outbreaks before and after imposition of control measures. Control always lowered the estimated dispersion parameter… This increased skew in transmission arose chiefly from undiagnosed or misdiagnosed individuals, who continued to infect others (and even cause SSEs), whereas controlled individuals infected very few. To further examine our control theories, we calculated and for each data set; $\hat{k}_c$ was always closer to $\hat{k}_c^{ind}$, although twice it fell between the two predictions, indicating a possible combination of control mechanisms (Fig. 3b). Real-world control thus seems to increase individual variation, favouring extinction but risking ongoing SSEs.

On the importance of data for testing the baked-in assumptions

We urge that detailed transmission tracing data be collected and made public whenever possible, even if unexceptional. At a minimum, we propose a new measure for inclusion in outbreak reports: the proportion of cases not transmitting ($p_0$), which, together with $R_0$ is sufficient to estimate the degree of variation in $v$ … Richer data sets may also enable testing of the branching process assumption that case outcomes are independent and identically distributed, by detecting possible correlations in $v$ values within transmission lineages or systematic changes as outbreaks progress.

Bat soup

High extinction probabilities indicate that disease introductions or host species jumps may be more frequent than currently suspected.

Further reading and thinking

This work must be integrated with established theory of sexually transmitted diseases and social networks, where high-risk groups exert nonlinear influence on R0 because contact rates affect infectiousness and susceptibility equally3,4,12,13,22.

Model and maths

Terms and distributions

$v$: individual reproductive number- random variable representing expected number of secondary cases caused by a particular infected individual

$R_0$: The, basic reproductive number, is then the mean of this distribution of $v$

Stochastic effects in transmission are modelled using a Poisson process $Z$

The distribution $Z$ of number of secondary infections is called the offspring distribution

- If $v = R_0$ constant, and there are discrete generations, then then $Z \sim Poisson(R_0)$

- In diff eq version with $v$ exponentially distributed, $Z \sim geometric(R_0)$ …

- Generally, if $v$ is gamma distributed with dispersion $k$ then $Z$ is has a negative binomial distribution

In all three candidate models, the population mean of the offspring distribution is $R_0$. The variance-to-mean ratio differs significantly, however, equalling 1 for the Poisson distribution, $1+R_0$ for the geometric distribution, and $1+\frac{R_0}{k}$ for the negative binomial distribution.

Negative binomial includes Poisson and geometric as special cases. Poisson when $k\to\infty$ and geometric when $k=1$. Variance is $R_0 (1+\frac{R_0}{k})$, so smaller $k$ indicates greater heterogeneity in spread.

The negative binimoial is a much better fit for empirically observed distribution of disease spread of SARS in singapore and China (PotthoffWhittinghill ‘index of dispersion’ test)

Superspreading and epidemic outbreaks

Definition of superspreading:

- estimate $R$ for the disease and population in question

- construct poisson distribution with mean $R$ (counterfactual with no individual variation)

- Define an $n$th percentile SSE as any individual who infects more than the $n$th percentile of the above poisson distribution

To assess the effect of individual variation on disease outbreaks, we analyse a branching process model with negative binomial offspring distribution, corresponding to gamma-distributed $v$

$q$: probability of stochastic extinction in branching model

For $R_0 < 1$, all invasions die out, same as standard models

For $R_0 > 1$, more variation “strongly favours extinction”

Example: If $R_0 = 3$ and $k=0.16$ (as estimated for SARS), then $q=0.76$. higher than with either poisson or geometric cases

Modelling interventions

Start with offspring distribution $Z \sim negativeBinomial(R_0,k)$ before control

Control parameter: $c=0$ is no control, $c=1$ completely blocks transmission

Population-wide control: infectiousness of every individual is reduced by a factor $c$. so $v_c^{pop} = (1-c) v$ for everyone.

Random, individual control: portion $c$ chosen at random are traced and isolated. so $v_c^{ind} = 0$ for portion $c$ of population and $v_c^{ind} = v$ for portion $1-c$ of population.

Population wide lowers heterogeneity, while individual raises it, measured by variance-to-mean ratio of $Z$. But both change basic reproductive number to $R=(1-c)R_0$. Threshold for garunteed extinction is the same in either case. $c \geq 1 - {1 \over R_0}$ But for intermediate values of $c$, invidual control works better. (Because higher variation favours disease extinction). Branching process theory: $q^{ind} > q^{pop}$ whenever $0 < c < 1 - {1 \over R_0}$.

If highly infectious individuals can be identified predictively then the efficiency of control could be greatly increased. Focusing half of all control effort on the most infectious 20% of cases is up to threefold more effective than random control… Gains in efficiency increase with more intense targeting of high-ν cases, but saturate as overall coverage c increases. Again, branching process theory generalizes these findings: for a given proportion c of individuals controlled, greater targeting of higher-ν individuals leads to lower effective reproductive number R and higher extinction probability q

Also, hey, nicely organized 31 page appendix.

EEeeeewwww:

A series of observational and experimental studies has documented the potential for upper respiratory tract infections (with a respiratory virus, e.g. rhinovirus or adenovirus) to convert nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus into highly infectious ‘cloud’ patients, so-called because they are surrounded by clouds of aerosolized bacteria25-28.

Imperfect disease control measures can increase variation in ν, if transmission is concentrated in a few missed cases or pockets of unvaccinated individuals10,20,34,37,42.